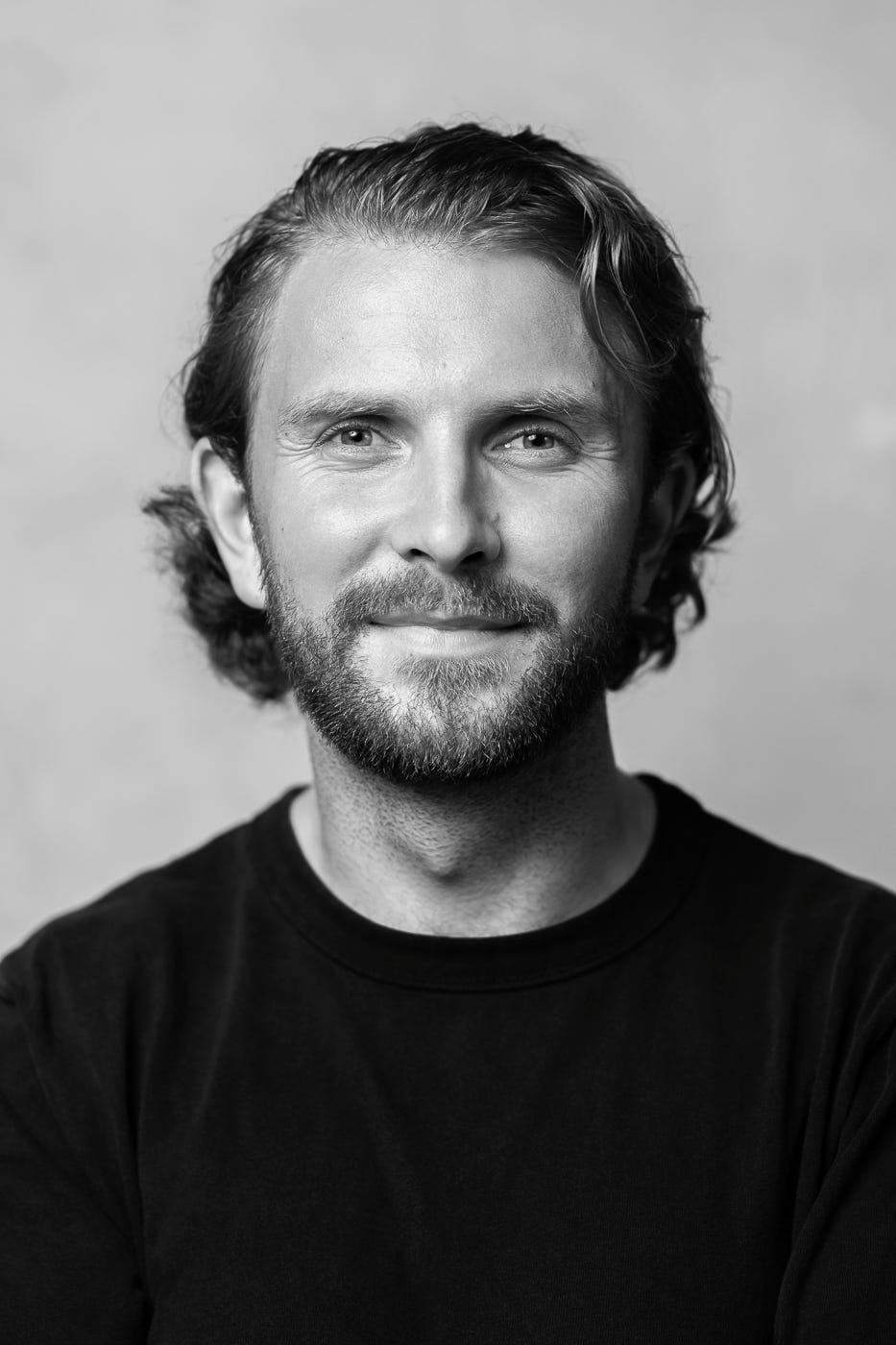

My chat with Finn Murphy, Partner at Frontline Ventures

"We were all smoking crack, and now we’re looking at the person who’s addicted and going, ‘what a moron.’ "

The last time I did a long chat with a venture capitalist was back in April of 2021 when I spoke to Semil Shah of Haystack Ventures. I have been meaning to do another similar wide-ranging chat with an investor in light of the new environment the startup world is living through now. It is difficult to find investors willing to share unfiltered, thought-provoking takes. I also wanted it to be a European investor. When I saw Finn’s piece on Sifted titled “It’s easy to blame founders, but should VCs have known better?”, I decided to talk to Finn about the current climate, American firms setting up in London, Ireland’s ecosystem, AUM expansion, why VC firms are products of homogeneous factory line production, and more.

Sar: I spent some time chatting with early-stage founders across London, Bangalore, and Singapore over the past few months. A common theme was how many first-time founders were going through cognitive dissonance.

It goes something like this “Our investors and board members supported and pushed for our aggressive growth plans until six months ago, and now they are advising us to do the opposite,” and “You claim to want to be the first call when things go south for your portfolio founders but refuse to offer more money at decent terms while advocating for us to extend our runway by two years.” I think this is a reasonable point of view for people who started companies in the past five years for the first time, are experiencing their first downturn in their adult lives, and are responsible for the livelihoods of their employees. Note that every single founder I spoke to had a top brand lead investor in their region or sector in their prior rounds.

Have you had similar conversations with founders? How do you help them process what’s going on, take it in stride, and start taking the steps necessary to be on a path to having a shot at long-term success?

Finn: Yep, I’ve had similar conversations. I advocated accelerated burn if it meant incremental growth increases in the heady times. Part of that was driven by knowing that there was capital available for companies and that capital efficiency wasn’t much of a consideration for investors until post-Series B. The whiplash founders are feeling now, and I’ve had to have these conversations, is those same investors (me) that gave one set of advice six months ago are sharing a different story now. Ultimately both extreme sets of advice are wrong. This new advice to be lean and extend the runway is driven by observing the markets, where the old advice to trade runway for growth came from in the first place.

Every company should be aware of the climate in capital markets. Still, ultimately, if you’re making the survival of your business contingent on that climate (which is changeable), you’re taking on an existential risk outside your control. The correct advice is, and almost certainly will always be, don’t make your business contingent on a frothy funding environment. Build products, serve customers, and grow. Make bets where you see opportunities for more growth but be aware that every move toward higher burn is another bet on building better products, serving more customers, and producing growth. Cutting burn allows founders to take stock of their bets and see what’s worth the risk.

Sar: You could make the case that founders are ultimately in charge, which would be correct. Ultimately, they don’t have to take the money at high prices and hire aggressively; they don’t have to do secondaries before building a stronger company, etc. Here's the free market argument from the prominent seed investor Semil Shah when I chatted with him in April 2021 :

Sar: There’s a lot of chatter about how the current pace & valuations are justified because markets are bigger than ever and the search for yields. Are we risking overcapitalizing an entire generation of companies for striking gold a few times?

Semil: I don’t know if we should worry about this. CEOs and founders have free agency to operate in the manner they choose. Many of them could go public earlier, but they choose not to often. Is that good or bad? I don’t know. For Snap, it was good! For others, maybe not be as good. Ultimately, it’s the founders and CEO who call the shots, and it’s a free market, and the capital sources (LPs) who bankroll these growth and pre-IPO funds keep the funds flowing, so why not?

I appreciate this line of thinking and agree that no one is forced to do anything! Everyone is playing the game as a rational actor. Founders are constantly told to make sure they have money in the bank! What do you think?

Finn: As CEO, I think it’s your job to make decisions. So if you raise at the high valuation, take the secondary, and hire aggressively pre-PMF - even if your VCs advise it. Ultimately it’s on you - this is why the CEO job is so hard. There is no authority to deflect to; you’re the final word.

The flip side is for VCs to take ownership of their bad advice and the bad options you present to founders. Was it the CEO’s fault for taking the crazy high valuation you gave them last year? Yes. Were you still stupid for making the offer at that price? Also yes.

Your job isn’t to tell the company what to do; it’s to present options from a financing perspective and a 10,000-foot high view. You see what happens across many companies at many stages. You can give anecdotes and views (sometimes ones that work in some markets but not others) - but you also own these.

Sar: You recently published a piece in the Sifted that echoes a common sentiment amongst many founders. It quite predictably didn’t make rounds on VC Twitter because of the position you took!

You wrote:

Look no further than the darling of European venture, Hopin, to see the blame game beginning. Once valued at $7.8bn, the virtual events platform has seen demand for its shares at nearly any price evaporate and had to enact major layoffs as in-person events come back into vogue.

Is the CEO responsible for not building a more sustainable business? Yes. Ultimately that’s your job in the top chair. Is he more responsible for this failure because he took over $200m in secondaries — selling part of his stake in the business — from hungry investors on the ride up? Absolutely not.

He didn’t force anyone to buy those shares. He didn’t force anyone to buy into the company at such a lofty valuation — investors could have said no. But many decided to partake as they were trapped in a self-imposed prisoner’s dilemma fuelled by FOMO.

It’s an investor’s responsibility to capitalise a business, build their position and manage that position. How you do that is your responsibility and yours to own, both when it goes right and when it goes wrong.

He didn’t force anyone to buy those shares. He didn’t force anyone to buy into the company at such a lofty valuation — investors could have said no. But many decided to partake as they were trapped in a self-imposed prisoner’s dilemma fuelled by FOMO.

It’s an investor’s responsibility to capitalise a business, build their position and manage that position. How you do that is your responsibility and yours to own, both when it goes right and when it goes wrong.

For the past 24 months, many investors have pushed a “growth at all costs” agenda in boardrooms everywhere. That made sense when the money was cheap and each incremental 50% added to your growth rate resulted in an extra 15 turns to your valuation multiple.

I’ll be the first to admit: I was a part of this. “The best way to raise your Series A is to start acting like you already have” was a strategy I rolled off like gospel.

Increase the burn. Acquire the customers. Damn the CAC/LTV (a measure of the lifetime value of a customer versus the cost of acquiring that customer): headline growth was king.

Why did you write this piece? What was the feedback from investors and founders? When I shared it the day you published it, I got a bunch of eye roll reactions privately from a few investors I know. They dismissed it as opportunistic content marketing to play the nice guy! I can see why they would think that. It goes back to the rational actors in the free market argument! On the other hand, I got a bunch of thumbs-up reactions from the founders, unsurprisingly! What would you say to the critics?

Finn: I wrote the piece because I’d been thinking about it. I’m pretty straightforward when it comes to working with founders, and I write stuff I think is relevant. When I heard about people getting screwed on share options in Europe, I wrote a piece on it.

So this was written from hearing in private VCs shitting on founders with high burns and who’d taken secondaries. We were all smoking crack, and now we’re looking at the person who’s addicted going, ‘what a moron.’ It just rubbed me the wrong way.

Feedback from investors was similar ‘yeh yeh another we should have known better piece.’ The rational actor’s thing is kinda bullshit as well - that’s fine when no one is pointing fingers, but once you’re in a blame game, look at the person using that argument to see who’s intellectually honest. If you’re like, ‘I was equally complicit by engaging in the game,’ then fine, but just look at the number of people who overpaid on stuff in 2021 being pious on Twitter now to know that’s not the case.

It was more straightforward from the founders - the piece came from discussions with my founders when we started discussing going out and fundraising or cutting costs earlier this year. People like to know how the other ‘side’ thinks, and I try to give that perspective to founders where I can.

Sar: Let’s switch gears and broadly talk about Ireland and Europe. Can you give us a high-level overview of Ireland through the lens of its startup ecosystem? What are some of Dublin’s underappreciated characteristics compared to other hubs like London, Paris, and Stockholm?

Finn: Ireland is a pretty interesting ecosystem - it’s a small home market, so if you’re going to build something big, you think internationally from day one. One of the challenges for the ecosystem up until recently was that often this meant the best founders moved to the US. Stripe and Intercom are great examples. That has changed recently - partially driven by big tech. Google employs about 7000 people in Dublin, and the city is only 1m. Of the working population, about 1 in 100 people work for Google. That’s not even counting Facebook, Microsoft, Linkedin, Hubspot, Stripe, Zendesk, and dozens of other tech companies with their European headquarters. Ultimately, I think the talent exists in Ireland to start and build a company from 1 to 10m in revenue. Beyond that, finding people with the know-how and ambition to build category-winning companies is tough. Workvivo & Tines are two good recent examples, but it’s still early days. An under-appreciated characteristic of Dublin is its cultural affinity for the US. We work hard and have a highly educated workforce that takes their work seriously, not themselves. It’s a great place to live and raise a family without being as insular or hierarchical as London, Paris, or Stockholm.

Sar: I met an American investor who recently moved to London to set up an office for his US-based fund. He told me he knows of at least 15 other Americans doing the same for their respective funds. Eric Newcomer has done some early coverage on this trend.

Here’s what he wrote:

For decades, startups in Europe were underfunded. Silicon Valley startups burned through billions while European entrepreneurs struggled to raise Series B rounds. That made it easy for European venture firms to cooperate with the Americans. They needed each other. “Europe historically had lacked enough funding, full-stop,” says Michail Zekkos, head of the London office at investor Permira.

A local firm might invest in a company’s seed round, then a larger local fund or even a pan-European venture firm would lead the A, and then, if all things went well, the Americans could come in around the B or C. That’s what happened with Spotify (Founders Fund) and Klarna (Sequoia). European venture capitalists were happy to see their deals marked up.

The beauty of that strategy is that American venture capital firms didn’t need to be on the ground in Europe. The American firms could monitor the continent’s Series A companies to see if there were any particularly promising global prospects. That made it relatively easy for the Americans to cooperate with even the blue-chip European venture firms like Index, Accel, Northzone, Atomico, Balderton, and Creandum.

What’s your take? What changes do you see in the ecosystem?

Finn: All the US funds have now raised so much money that they’ve run out of deals to stuff cash into at home. That’s why they are spinning up offices to go after the earlier opportunities in Europe.

Sequoia had its first fact-finding trip to Dublin last year. Lightspeed is poaching young up-and-coming investors from funds in Germany. Coatue is dropping its cash cannon on talent in London and across the continent. It’s great for the seed funds and the ecosystem, as Eric Newcomer’s assessment is correct. Europe was still massively short of growth capital, partially because there weren’t enough opportunities to sustain a dedicated investing business.

With more funds operating earlier, we’ll see a better pipeline of quality companies for these growth funds to invest in. Hopefully, those companies will generate liquidity and kick off the flywheel of returns that Europe desperately needs.

Sar: We will discuss this topic later in the broader and spicier conversation about AUM, hiring, and the willingness to look stupid. Let’s talk about Frontline now. You guys invest in B2B companies with global expansion plans. What are some common pitfalls European companies run into when they plan and execute expansion into North America? There are people problems, cultural differences, go-to-market localization, product customization, etc. Are there sectors where the transition is particularly hard? I’m most familiar with fintech, and it's been brutally hard for late-stage players to cross the Atlantic in either direction.

Finn: Thinking you can drop someone from the US office in Europe with no network or cultural context is a classic error by many companies. Opening your first international office is scary from a cultural point of view. But you need to commit to the continent - first to a major city - the only viable three for US companies are Dublin (Great Inside Sales Talent from all the existing EMEA HQs) - London (Where a lot of Enterprise customers are based & there’s strong engineering talent) - Amsterdam (Travel tech hub from Booking.com and others). It’s hard to get right, so we raised a fund dedicated to helping companies figure this out.

Fintech is brutally hard to internationalize. While Europe looks like one market, it’s 28 different ones with some commonalities. Doing business in Germany is very different from Spain. You need deep knowledge of the mechanics of the country's regulators and their consumer quirks (Germans love cash etc.) - It can be done - but it requires a pretty considered approach, and it’s hard to justify investing if you’ve still room to grow in the US.

Sar: Do you see American companies trying to enter Europe a lot earlier in their lifecycle now versus 3-4 years ago? What do you see American founders and investors consistently under-appreciate or misunderstand about expansion into Europe?

Finn: If you need to grow, the international markets are a key lever - on average, 30% of US SaaS companies at IPO come from EMEA, so you can’t wait for it for too long. With the demands on growth in recent funding times, it’s been even more important.

The biggest thing I probably see is underestimating both the opportunity and the challenge. It will not be easy, but it could also be your fastest-growing market. I spent a bunch of time with the Fivetran team when they were getting set up in Dublin, and within a year, it was their fastest-growing market and had most of their top-performing AEs. But it had proper buy-in from the founders and a great champion to head the office who hired strong local talent early. Old lessons that are always true if you’re going to do it. Do it right.

Sar: It is common to see a version of the following exchange on Twitter. Where do you fall on this debate?

Finn: Lol - yep - Americans want maniacs, and Europeans want business people. Ultimately I’ve seen bad investors on both sides of the Atlantic. Some Europeans are still operating on an old-school mindset. Partially because fewer of them come from an operating or founder background - only 8% of EU VCs have founded or worked in a VC-backed startup - which is a lol.

I think every investor has things that are important to them. Incremental thinking leads you to think about the details around channels and financial models. Exponential thinking has you figure out if the person you’re talking to is insane enough to build a multi-billion dollar company. You can ask good questions to figure out both, and you can also be a dick. It just depends on how and what you ask.

Sar: Let’s switch gears. I find it quite amusing that so many VCs suck at doing things they advise their portfolios to do well all the time. One of them is managing people.

Finn: I've met a lot of really good investors who are bad at the venture business. And now I've met people who are good at venture business and bad investors. There's being able to pick good companies and then creating the environment where you are more likely to pick good companies and create great returns.

Sar: Do you mean firm management?

Finn: Right. Yeah. And some people are just really good at going out and finding the next Stripe. But those people can be terrible at hiring. They can be terrible at management. There’s nothing wrong with that, necessarily. It’s why most success stories are firms. You need a balance of people over time.

Sar: What’s your perspective on the ongoing AUM expansion of the big brands and the never-ending debate of whether founders should take seed money from multi-stage firms?

Finn: All the multi-stage firms have grown their AUMs significantly and have expanded teams aggressively. They are doing many seed deals partially because they've hired many young talented people. They have to do something. GPs don't want them writing big checks; they’re like, you can learn by doing a bunch of seed deals.

In addition, those young people, by nature of getting those jobs, are now highly sought after. And if those people are good and you don't let them do deals, they'll just go elsewhere. It’s not the only reason the big funds do more seed investing. But it’s another pressure wave in the industry that impacts investing behaviour. Just like lower rates led to bigger funds, bigger funds led to bigger investing teams, and bigger investing teams led to larger portfolios up and down stages.

I'm not totally opposed to people taking seed money from the big multi-stage funds. The good news is if that's one of their first few seed deals or the first seed deal in new geo, their reputation is tied to you, so they want to make you successful. The downside is they might not be there, or they might not have the clout to fight for you in the next round. If the founders have all the information and they make a decision, it’s totally fine. Just know what you’re getting into.

Sar: Talk about your thoughts on the American brands setting up offices in London in the context of the AUM story.

Finn: So a part of this boils down to growth in AUM. I'm European, so I'm saying this from a European angle. Suppose you have a choice between investing in the top quartile of US startups and top quartile European startups from a purely quantitative point of view. In that case, you will put all your money in the US bucket because, on average, that bucket outperforms the European one. Don’t get me wrong, there are amazing European companies, and you can generate great returns. But on a basket of averages, if you can access the top of the market in both - the US wins. Access is an important word.

So, why are Sequoia, Lightspeed, ICONIQ, Bessemer, Coatue, and General Catalyst setting up European offices? It's because the top quartile in the US is so saturated now. There's so much money that it’s harder and harder to access that bucket at entry prices where you can generate great returns. This is where comparatively interesting opportunities crop up in Europe. Also, certain categories, deeply technical & fintech/regtech, for example, have the talent & regulatory capture advantages that greatly favour the next big thing coming from Europe.

It’s just another downstream impact of AUM. First, you go multi-stage, then multi-sector, then multi-geo, then multi-asset (FoF, liquid/publics, etc.), and now you’re a full-stack firm. Why wouldn’t you, if you’re a GP and can raise a $3 billion fund? (actually, loads of reasons, but it’s very hard to say no to all those fees).

It’s a testament to the discipline of smaller funds like the USV, IA, and Benchmarks who haven’t scaled teams or AUM. The downside is that a small team’s generational transition is even harder. When you only add 1 GP every ¾ year, you put adverse pressure on the firm to get that right. Making the likelihood of delaying it at your peril much higher. There’s an element of damned if you do, damned if you don’t. Ultimately, it’s hard not to become an AUM shop, but once you're an AUM shop, you need to have this multi-everything approach. Products for yee, products for thee.

Sar: Right, You just have to do everything. And at some point, you have to believe that we need to keep hiring more Stanford grads. Fundamentally, it's a linear business. There's only so much time in a day, so it’s a headcount problem.

Finn: It's a headcount problem to an extent. I’ve seen similar-sized teams managing 250m as managing 2.5B, so you can solve some of the scaling problems by writing bigger cheques. It’s much harder to scale the returns (multiple & IRR) while also growing the AUM. On the hiring front, I've talked with a few people about the Stanford grads/tick the boxes persona thing, and I have a rough assumption around firm career risk/recency bias that causes much of the cookie-cutter approach to junior VC recruiting.

Growth in AUM triggers this series of events that results in Sequoia opening an office in Europe. And you can tell the story to do that, and that's fine - it’s a risk to do anything outside the box in a big firm. Opening that office was no different. It’s not ‘buying IBM.’ These factors play in venture firms too.

A version of “nobody gets fired for buying IBM” also plays out in recruiting. Many people entered the venture business by ticking many right boxes. Those boxes (Harvard, Stanford, Palantir, etc.) signal high ambition & competitiveness in young people. Those are key skills for climbing the VC totem pole.

Sar: Yeah, that makes sense. I don’t think that fully explains what is going on, though. There are plenty of ambitious and competitive people. I would argue the ones that didn’t get a chance to be at those well-branded institutions often have a chip on their shoulders. Talk about your theory of lack of willingness to look stupid in political organizations explaining much of what is going on.

Finn: A superpower in the venture is to be comfortable looking like a complete moron. You have to be willing to look stupid occasionally because many of the best investments look stupid at some point. And on the best ones, you get the last laugh. You actually will look stupid on the majority.

Statistically, half of your investments are going to lose money. As the AUM grows and you get more political with larger organizations, it becomes harder and harder to do things where there's a high likelihood of you looking stupid. If you're Peter Fenton, you can do something stupid now because you’ve already done Hortonworks, Cloudera, and Elastic. But you’re on the tightrope until you’ve got a pocket full of bangers.

Doing something that looks stupid is often not politically advantageous once organisations grow in size and become more hierarchical. For example, nobody's getting fired for starting an accelerator program that doesn't deliver results because it logically makes sense. What are we trying to do? We're trying to increase deal flow. We're trying to see companies earlier, and we're trying to build more networks in various geographies. Is it something you’ll look stupid for doing if it doesn't work out? Not really. Hiring outside the ‘known quantity in one of these firms is also about the willingness to look stupid. What happens if someone doesn't work out?

Everyone’s trying to be a GP. Everyone knows the way to become a GP is to do an absolute banger, then use the leverage from that with the rest of your partners to be brought in. If they don’t, you can leave. This is why people fight for deal attribution. All the LPs have to know that you were the person that made money. That's a key part of a firm’s leverage in career building. Often, the GPs are not doing the more junior/entry-level hiring. That's now delineated to another layer of junior partners, particularly in the bigger firms. For those people hiring someone who turns out to be great is another thing that can massively boost your career within the firm. But it’s not as beneficial as nailing a great investment, and the downside of hiring a dud is much higher than the upside of them being fantastic. So you resort to hiring the ex-Morgan Stanley Harvard-educated or ex-Mckinsey Stanford person. It wasn’t a stupid decision if that person didn’t work out.

LPs don't really like change, so it's the bigger funds that are the people who can afford to take the most risk from a capital base point of view. But they can also often be the most risk-averse because of their political structures. This is just how it is and likely the way it will be. Once you embrace that, it’s more fun. The quote I go back to on all things is, ‘Life isn’t about being good at the game; it’s about figuring out what game you’re playing.’ Once you observe the rules in VC, you have to work them to get a job and excel. Hard to change them until you’re on the inside.

Sar: Let’s end with a fun topic. What cultural artifacts or entertainment would you recommend to people looking to learn about the culture of Ireland?

Finn: Ireland used to be very Catholic, and the turning point against the church’s power was the late 90s. A sitcom called Father Ted emerged about three priests banished to work on an Island off the coast of Ireland because of their quirkiness. It’s weird and might make no sense to someone without the cultural context, but it’s iconic in Irish culture. There’s also the classic and one of the most streamed rock songs of all time, Zombie by the Cranberries. It’s all about the conflict in Northern Ireland, young people's oppression, and their feelings. It’s also a banger.

Chats from last week :